Featured Image: Playas de la Costa Verde, near Lima, Peru. Photo Credit: Willian Justen de Vasconcellos, Unsplash.

A strength of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill is the potential for students to take courses in other departments and engage with faculty and students across the university. This interdisciplinary education is critical for planners-in-training. Planning, more than most professions, requires engaging with cross-disciplinary issues and obligates practitioners to serve as facilitators on teams with diverse backgrounds and expertise. Thus, the opportunity to engage in high-quality academic research on a multidisciplinary team as a student is an invaluable experience in graduate school.

Two DCRPers engaged in this opportunity in spades during the spring 2019 semester. First-year graduate students Emily Gvino (MPH/MCRP) and Leah Campbell (PhD) were members of a five-person team brought together for a semester-long research seminar with the goal of developing a paper that could eventually be published. The theme of the GEOG 803 class, hosted by the Department of Geography, was climate change and health, broadly interpreted. One group in the class focused on the impacts of climate change on agricultural yields in the Southeast United States. Another looked at deforestation and forest livelihoods in Central Africa.

Emily and Leah’s team looked at the impacts of long-term climate change on the prevalence of stunting for children under five in Peru. This research is highly related to Emily and Leah’s academic interests: Leah focuses on integrating equity and resilience into climate adaptation, and she possesses a background in geophysics and environmental science. Emily’s research interests involve how the natural environment can address social justice issues and the impact of climate change and the environment on health.

Stunting is defined by a measured height-for-age two or more standard deviations below the international median determined by the World Health Organization. As a nutritional health outcome, stunting is a critical condition to study because of its association with several subsequent health and social outcomes. The negative repercussions include an increased risk of death, poor adult health, reduced cognitive function, decreased fine motor skills, and decreased lifetime economic productivity and earnings. As of 2011, more than 165 million children under five were stunted worldwide; an additional 25 million are projected to be undernourished (and therefore stunted) by 2050, with projections connecting these results to climate change.

Peru is a particularly interesting place to investigate stunting trends given the overall high rates of stunting nationally. As a result of both pervasive poverty and social inequality, as well as economic and political instability through the 1980s, Peru previously had one of the highest rates of stunting in Latin America. As of the early 2000s, more than a quarter of children in Peru were stunted. Specifically, the Peruvian government ventured on a country-wide, coordinated effort to rectify the public health crisis, which had not improved despite the concurrent economic growth in the region. In particular, the government focused their policy and intervention efforts on improving nutritional outcomes; this program was the most effective on the part of the Peruvian government in two decades, reducing the rate of stunting by 11.7 points in only six years (from 29.8% in 2005 to 18.1% in 2011). The findings from their paper, by examining the connection between climate anomalies and stunting in Peruvian children, may illuminate if these continued governmental efforts will be undermined by climate change in the coming years.

Given these interesting trends, many studies have looked at the relationship between different demographic characteristics and stunting in Peru. The results are consistent with other studies that have been done through the developing world. Unsurprisingly, the highest rates of stunting are typically found in the poorest households, those most dependent on agriculture, located in rural communities, and present in families where mothers have the least number of years of formal education. In Peru, specifically, indigeneity has been found to be another important predictor of stunting with a stunting rate of 47% in indigenous communities versus only 23% in non-indigenous households.

Plenty of research has also been done on the ways in which climate change may increase the prevalence of stunting globally and exacerbate the socioeconomic disparities in stunting rates. Three main mechanisms have been proposed for how climate may impact child height. The first is that fetal stress will permanently inhibit child growth if a mother is exposed to climate extremes while pregnant. However, that finding ignores the potential of ‘catch-up’ growth after the earliest development stages. The second is that climate anomalies will change agricultural productivity, in turn negatively impacting family incomes and food availability. This argument is complicated by individual and household-level adaptation and non-environmental drivers of agricultural productivity including prices and market access. The final proposed mechanism is that climate change will reduce water quality and change the disease environment, increasing the prevalence of diarrheal and gastrointestinal illnesses that can inhibit growth in children at critical early stages.

Emily and Leah’s paper this semester focused less on the specific pathways than simply what impact climate change may have on Peruvian children’s health outcomes. This connection represents a notable gap in the literature to-date. This analysis was also somewhat unusual in its method. Rather than trying to investigate the relationship indirectly (many previous studies looked at climate impacts on agriculture and then made assumptions as to the impacts on child nutrition), this paper looks at the direct relationship between temperature and precipitation anomalies and height-for-age scores, without making assumptions as to the nature of that relationship.

Using data from the global Demographic and Health Survey, one of the most important datasets in public health research, regression models were developed to look at how year-to-year exposure – including prenatal exposure – to climate anomalies predicted the likelihood of stunting. Both a logistic regression (with the WHO standard cut-off for the stunting determination), and a linear regression (using height-for-age scores as the outcome variable) were developed, controlling for various socioeconomic characteristics at the household and child level, including maternal education and age, child age and sex, family wealth, indigeneity, and geography. The sample of children – almost 80,000 records – were then divided into five cohorts based on age to examine whether the effect of climate differed based on a child’s age.

Results are still being analyzed, but the initial findings are promising for a publishable paper. In line with previous studies, findings confirm that larger households with lower socioeconomic status or in indigenous communities are more likely to have stunted children. Interestingly, young boys were found to be more at risk of stunting than girls. This is a common finding as well, though no satisfying social or biological reason has been found to explain it.

Where the study gains intrigue is what it suggests about climate impact on stunting. While increasing rainfall was actually found to have a positive effect on children’s height, there is a clear relationship between increasing temperatures and increased rates of stunting. Interestingly, children don’t seem to be affected by the most recent year of climate exposure; that is, kids in the 4 to 5-year-old cohort were not significantly affected by temperature anomalies experienced in their 3rd to 4th years of life. It’s difficult to know the cause of this finding in the scope of this analysis; it’s possible that there are delays between temperature extremes, reduced food availability because of temperature, and poor nutritional outcomes because of reduced food availability or quality.

Figures 1 and 2. Monthly mean precipitation (1) and temperature (2) values for each region, represented by five month moving averages over the years 1981-2012. Regional monthly means were calculated using weighted averages over polygon size for departments located in each region. Vertical lines represent the first months of years with very strong El Niño events as defined by the Oceanic Niño Index index.

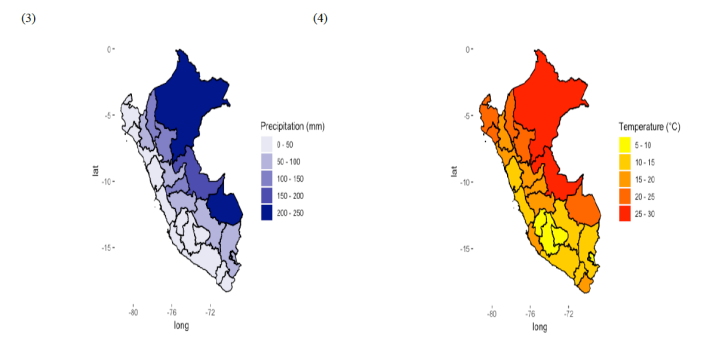

Figures 3 and 4. Overall monthly average for precipitation (1) and temperature (2) across Peru departments over the 1981-2012 year period.

Another particularly interesting finding is that the effect of climate experienced in utero on stunting rates, though significant in the first couple of years of life, dissipates after age three. The positive explanation for this is that children experience ‘catch-up’ growth over time. The more negative interpretation is that children most dramatically affected by fetal stress die early and are, thus, lost from the sample. The issue of selective mortality was beyond the scope of this analysis but represents an important issue to explore in the future.

The team is wrapping up its first draft of the analysis and paper currently. After this semester, they hope to continue working together to move the project forward towards publication. The most immediate goal is to expand the regression models to include interaction terms between the climate variables and some of the socioeconomic/demographic variables. This will allow the team to elucidate any direct relationships between these characteristics and climate to determine whether climate change will disproportionately affect some groups and whether the negative effect of certain characteristics, like poverty is exacerbated by climate change. After that point, it’s a matter of preparing the paper for submission in a publication, which will undoubtedly bring its own challenges and opportunities!

The full team on this project includes: Leah Campbell (Department of City and Regional Planning, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill); Khristopher Nicholas (Department of Nutrition and the Carolina Population Center, UNC-CH); Emily Gvino (Department of City and Regional Planning and Department of Health Behavior, UNC-CH); Gioia M. Skeltis (Department of Anthropology, UNC-CH); Wenbo Wang (Department of Statistics, UNC-CH)

References:

Marini, Alessandra, and Claudia Rokx. 2016. Standing Tall: Peru’s Success in Overcoming Its Stunting Crisis. Public Disclosure. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28321.

Mejía Acosta A., and L. Haddad. 2014. The politics of success in the fight against malnutrition in Peru. Food Policy, 44:26-35.

Huicho, L., Huayanay-Espinoza, C. A., Herrera-Perez, E., Segura, E. R., Niño de Guzman, J., Rivera-Ch, M., and A. J. D. Barros. 2017. Factors behind the success story of under-five stunting in Peru: A district ecological multi-level analysis. BMC Pediatrics, 17(29):1-9.

Johnson, K., and M. E. Brown. 2014. Environmental risk factors and child nutritional status and survival in a context of climate variability and change. Applied Geography, 54:209-221.

Larrea, C., and W. Freire. 2002. Social inequality and child malnutrition in four Andean countries. Public Health, 11(5-6):356-364.

Lloyd, S. J., Kovats, R. S., and Z. Chalabi. 2011. Climate change, crop yields, and undernutrition: Development of a model to quantify the impact of climate scenarios on child undernutrition. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(120):1817-1823.

Phalkey, R. K., Aranda-Jan, C., Marx, S., Hofle, B., and R. Sauerborn. 2015. Systematic review of current efforts to quantify impacts of climate change on undernutrition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 112(33):4522-4529.

Prendergast, A., and J. Humphrey. 2014. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Pediatrics and International Child Health, 34(4):250-265.

Shin, H. 2007. Child health in Peru: Importance of regional variation and community effects on children’s height and weight. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48:418-433.

Tiwari, S., Jacoby, H. G., and E. Skoufias. 2017. Monsoon babies: Rainfall shocks and child nutrition in Nepal. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 65(2):167-188.

Woldehanna, T. 2010. Do pre-natal and post-natal economic shocks have a long-lasting effect on the height of 5-year-old children? Evidence from 20 sentinel sites of rural and urban Ethiopia. Working Paper 60. Young Lives: An International Study on Childhood Poverty. Department of International Development, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK. 49pp.