By Joseph Womble

In mid-October, I had the privilege of being able to attend the North Carolina chapter of the American Planning Association (NC-APA) conference along with planning practitioners from across the state of North Carolina and many of my fellow DCRP students. As first-year master’s students, NC-APA was our first major opportunity to attend a conference relevant to our coursework and planning more broadly.

Perhaps my biggest takeaway from the conference was how many communities in North Carolina are undertaking innovative planning projects. As a planning nerd even before graduate school, I was aware of large ongoing projects in major U.S. cities, and even some in North Carolina municipalities, such as Raleigh’s bus rapid transit corridors. However, I was not aware of the many smaller communities that are on the cutting edge of everything from resilience planning to artificial intelligence.

For example, NC Highway 12 (NC-12) is the only North-South corridor that runs through the Outer Banks and is therefore critical for evacuation during emergencies. The route faces repetitive flooding due to sea level rise and extreme weather events. The Town of Duck, in partnership with a host of organizations at the local, state, and national level, has completed a resilience project for a portion of NC-12 that runs through their community.

This project consists of three main parts: a “living shoreline,” elevation of a portion of the roadway, and the addition of sidewalks and bike lanes. It keeps the town’s focus on resiliency central, while also integrating other mobility options for residents and visitors to experience Duck’s coastline.

While Duck has a significant influx of population during tourism season, the town only has 800 full-time residents, so its resilience project stands as an impressive example of what smaller communities can achieve through partnerships with state, federal and local agencies and planning consultants.

Across the state from Duck, Buncombe County recently completed its first comprehensive plan, which included an explicit focus on equity from its conception. From the initial Request for Proposals, the county identified equity as a key goal and made it clear that respondents should share that commitment to be successful in their response.

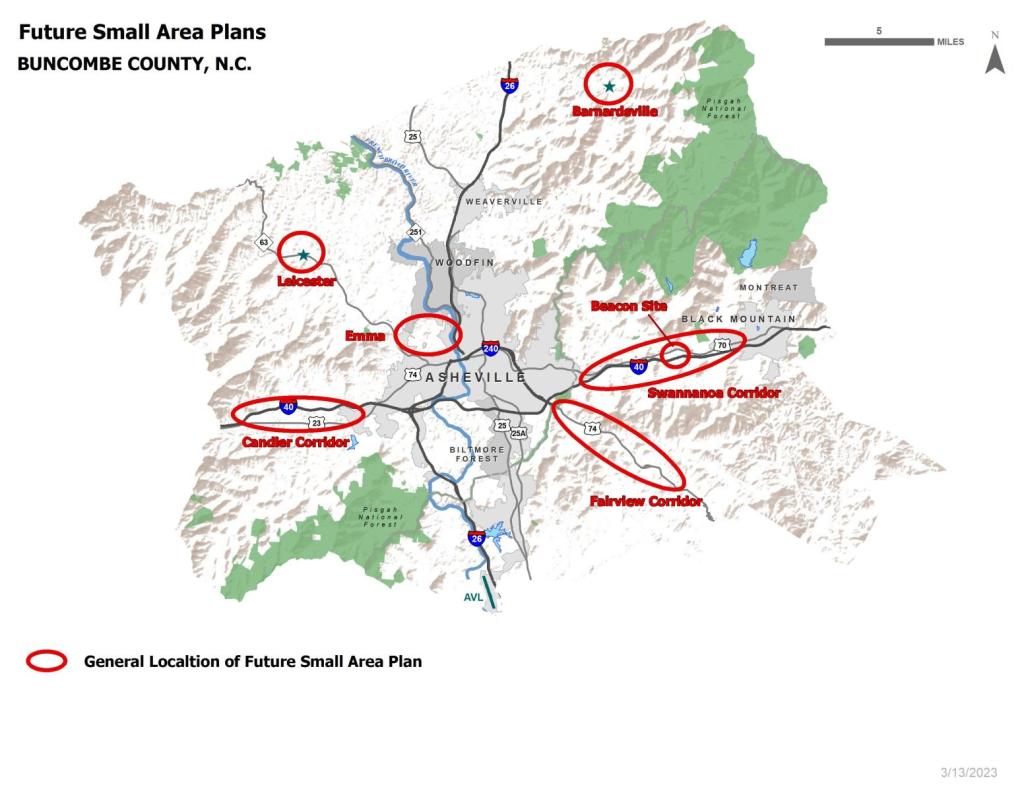

The comprehensive plan also established “small area plans,” which were areas with vulnerable populations or that were facing significant gentrification pressure on which the county wanted to focus. Various tools and strategies, such as a Community Index Map, an Equity Analysis Tool, and creating ‘equity check-ins’ for those involved in project review and evaluation helped the county cement their commitment to equity in their comprehensive plan.

Another key lesson that emerged for me from NC-APA is that there is real value in committed professional planners who know their communities and how to speak to their concerns. Planners often must navigate the challenge of an asymmetric information ecosystem, bringing technical and political knowledge to bear in the context of peoples’ lived experience. Planners from the City of Raleigh shared their perspectives in a session titled Restoring Faith in Planning: Implementing Plans through Proactive Zoning Changes, arguing that planners have largely lost their boldness, forgotten the tools they have on hand to concretely improve their communities, and have focused on constant plan-making rather than implementation to the detriment of collective goals.

Perhaps, as someone new to the professional planning space, I am used to what I consider planning best practices feeling contentious because I have observed them in the local political process. In the context of NC-APA, however, there seemed to be broad agreement about the problems that communities face and potential solutions. I know that differences in opinion among planning practitioners are common, but it was refreshing to observe planners discussing best practices to improve communities and thinking about “what’s next” rather than relitigating facts or an overall problem statement.

NC-APA was in Greenville, NC this year, a city with a rich history in commerce and education and with a convention center located on a high-speed corridor without sidewalks, crosswalks, and housing. Even though my hotel was a 15-minute walk from the convention center and it was nice weather while I was at the conference, I had no choice but to drive my vehicle to the convention center unless I wanted to quite literally risk my life.

While it is deeply inspiring to see examples of best practices from other U.S. cities and across the world, the location of NC-APA was grounding and a constant reminder of the substantial work that remains. A discussion of potential solutions for these corridors came up in multiple sessions, including in the context of the creation of ‘grand boulevards’ – transforming the classic American wide road with strip malls into mixed-use development with multiple mobility choices.

I am already looking forward to attending NC-APA next year and learning more about other projects going on in communities across the state. This conference was immensely helpful in better understanding the overall landscape of what it is actually like to practice planning in North Carolina, and it reminded me of why I wanted to become a planner in the first place: to make a concrete difference in communities and in peoples’ lives.

Joseph Womble is a first-year student in the Master’s of City and Regional Planning program at UNC Chapel Hill. His studies focus on transportation systems and their intersections with housing and broader land use. Previously, he was a Research Analyst at World Resources Institute, where he provided technical assistance to local governments seeking to advance clean energy and clean transportation goals.

Edited by Joe Wilson

Featured image courtesy of Greenville Convention Center